The words "low-carb" and "keto" get thrown around a lot. Are they the same thing?

At first glance, it may appear that if you eat one less cup of rice, you can transition from a low-carbohydrate diet to a ketogenic diet. After all, both nutritional strategies place an emphasis on reducing carbohydrates, and both are often followed for their fat-loss potential. Pretty much the same thing, right?

Not so fast, ketobro. Although both diets are considered low-carb compared to the standard Western diet—you know, the one made up mostly of processed carbs and mystery ingredients—the similarities stop there, both in philosophy and execution.

Here's what you need to know about low-carb and ketogenic diets so you can make an informed choice!

The Low-Carbohydrate Diet Defined

A low-carbohydrate diet is a pretty vague description in and of itself. After all, "low" is a relative term. But in the most effective versions of this approach, the priority is being more selective about your carbs and where they come from.

In many cases, you can still eat fruit, vegetables, and beans, while eliminating or cutting back on grains, baked goods, and processed sugars. This shift from carb-dense sources to low-density ones naturally reduces the daily amount of carbs you take in.

However, a low-carbohydrate diet lacks specific classifications of what "low" means, and often neglects protein and fat recommendations. Technically, if you're used to eating 300 grams of carbohydrates per day, and drop to 200 per day, you're following a lower-carbohydrate diet. If you don't replace those lost calories, you'll probably lose some weight, but it may have been the lower calories that caused it, not the lower carbs. Conversely, if you replace those missing calories with either more fat or more protein, you produce two very different diets.

It's safe to say that this approach has many potential interpretations—and outcomes.

The Ketogenic Diet Defined

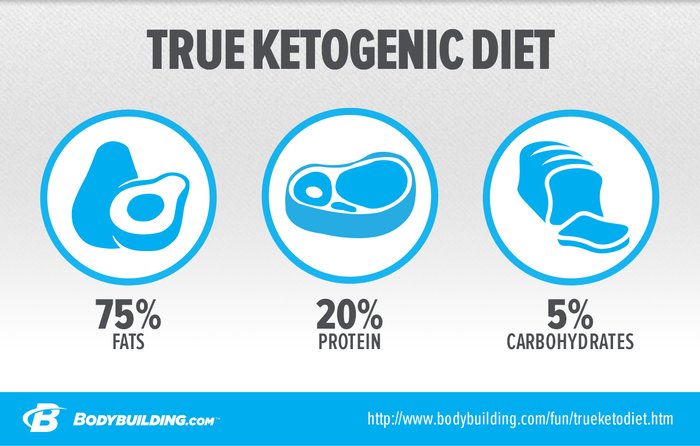

While a diet can become low(ish)-carb merely by cutting back on a single macronutrient, a ketogenic diet demands specific changes to all three macronutrients. For this reason, it's hard to recommend a keto diet to someone unless they know how to track their macros or are serious about learning.

A ketogenic diet is a high-fat, very low-carbohydrate, moderate-protein approach that, when done correctly, shifts your body's preferential fuel source from carbohydrates (or glucose) to fat in the form of ketone bodies and fatty acids.[1]

For a diet to be ketogenic, it also has to be pursued with the end goal of putting you in a state of nutritional ketosis. This is a very specific state, and unless you know what you're doing as you aim for it, you can end up feeling pretty miserable and see your training go down the tubes. So let's dig deeper into the details.

The Difference Is In The Ketones

One byproduct of carbohydrate restriction is increased production of ketone bodies, which are small molecules derived from fat produced in the liver. When your body's stored glucose levels are low, ketone production increases. This can be measured via blood- or urine-ketone testing.

A traditional high-carb diet results in blood ketones between 0.1 and 0.2 millimoles (mmols), and a moderate-to-low-carb diet has no significant effect on this. However, once you truly embrace a ketogenic diet, blood ketones rise to 0.5 -5.0 millimoles, putting you in a state of "nutritional ketosis" and signifying that you're keto-adapted.[2] This is the primary indicator that you're following a ketogenic diet.

So how does this all translate to macros? Let's take a look.

Carbohydrates

In most research studies, a low-carbohydrate diet is defined as eating less than 30 percent of calories from carbohydrates, which often equates to 50-125 grams per day.[3,4] For comparison's sake, The American Dietary Guidelines (2010) recommend that 45-65 percent of calories come from carbohydrates each day.[5]

A ketogenic diet, on the other hand, is defined as eating 5-10 percent of total calories from carbohydrates.[6] This often equates to 25-30 grams of carbohydrates per day, with a suggested maximum of 50 grams per day.

Keeping your carbs consistently below this 50-gram threshold appears to be the trigger that induces nutritional ketosis and enables your body to begin relying primarily on fat as fuel.

Protein

Protein intake can run the gamut in a low-carb approach. Personally, when weight loss is the goal, I recommend maintaining a moderate to high protein level to support muscle mass and satiety.

- High-protein diet: Greater than 0.7 grams per pound of body weight

- Moderate-protein diet: 0.36 - 0.69 grams per pound of body weight

- Low-protein diet: Less than 0.36 grams per pound of body weight

This recommendation doesn't extend to a ketogenic diet—and this is one of the most common mistakes fit people make when they transition to keto. Eating too much protein—more than 0.67-0.81 grams per pound of body weight, according to Dr. Jacob Wilson, director of the Applied Science and Performance Institute—when following a ketogenic diet will kick you out of ketosis.

You know that too many carbohydrates will kick you out of ketosis. Now you know that too much protein will, too. This is because when carbohydrates are low, protein can also be broken down into glucose via a process known as gluconeogenesis. Eating too much protein—more than 20-25 percent of daily calories—increases gluconeogenesis, and therefore glucose production, ultimately blunting ketone body formation.

Fats

A well-designed low-carbohydrate diet should still have a moderate amount of fat—you have to fill your calories somehow, right? Far too many physique competitors have discovered the hard way that going low-fat and low-carb leads to poor recovery and feeling awful most of the time. That said, provided you're getting the minimum, your fat level isn't as crucial in a low-carb approach, since your body is still running off of carbohydrates as its primary fuel source.

On a ketogenic diet, however, everything hinges on fat. A whopping 70-75 percent of your daily calories are supposed to come from fat, because it is now your primary fuel source.[6] When eaten in the absence of carbohydrates, fat is used as a readily available fuel source.[7]

This can be hard for many people to commit to, but research increasingly supports the idea that dietary fat isn't what makes you fat. A high-fat, high-carb diet, conversely, is the true culprit for many obesity-related issues.

Which Diet Is For You?

This is a personal question. Some people get into ketosis and never feel right. Others discover it's exactly the feeling—and the results—they've been after all along.

Both diets are useful weight-loss strategies and have research to support their ability to promote weight loss (given that you're in a caloric deficit, of course). What works for you may be largely a question of taste and lifestyle. For what it's worth, low-carb with a moderate-to-high protein intake probably requires fewer drastic changes to your current diet and shopping list than going keto.

Most importantly, don't throw yourself into a severely low-carbohydrate diet that's not low enough—or high-fat enough, or low-protein enough—to kick you into ketosis. This is a recipe for hovering in that unpleasant tweener zone known as the "keto flu," where your brain and other systems are searching for fuel but can't find it. It's a recipe for bad workouts, foggy work days, and rampant cravings.

In a strict ketogenic approach, the first few weeks of becoming keto-adapted can be rough, but it's short-lived if you set up your diet correctly. Take your pick, track your macros, and pass the grass-fed butter!

References

- Volek, J. S., Noakes, T., & Phinney, S. D. (2015). Rethinking fat as a fuel for endurance exercise. European Journal of Sport Science, 15(1), 13-20.

- Phinney, S. D., Bistrian, B. R., Evans, W. J., Gervino, E., & Blackburn, G. L. (1983). The human metabolic response to chronic ketosis without caloric restriction: preservation of submaximal exercise capability with reduced carbohydrate oxidation. Metabolism, 32(8), 769-776.

- Bueno, N. B., de Melo, I. S. V., de Oliveira, S. L., & da Rocha Ataide, T. (2013). Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Nutrition, 110(07), 1178-1187.

- Nordmann, A. J., Nordmann, A., Briel, M., Keller, U., Yancy, W. S., Brehm, B. J., & Bucher, H. C. (2006). Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(3), 285-293.

- Institute of Medicine, 2002. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press.

- Masino, S. A., & Rho, J. M. (2010). Mechanisms of ketogenic diet action. Epilepsia, 51(s5), 85-85.

- Sidossis, L. S., & Wolfe, R. R. (1996). Glucose and insulin-induced inhibition of fatty acid oxidation: the glucose-fatty acid cycle reversed. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism, 270(4), E733-E738.